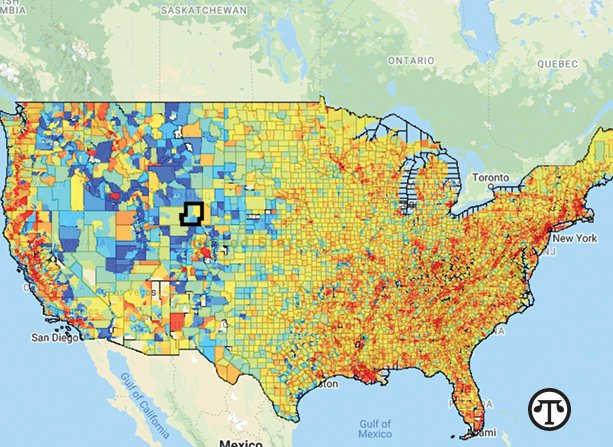

Across The U.S., Non-white Neighborhoods Are Hotter Than White Ones

(NAPSI)—Nationwide, in both major cities and small towns, neighborhoods with more Black, Hispanic and Asian residents experience hotter temperatures during summer heatwaves than nearby white residents, regardless of a neighborhood’s income.

These racial disparities exist because non-white neighborhoods tend to be more densely built up with buildings and pavement that trap heat, and have fewer trees to cool the landscape, according to the nationwide study in the AGU journal Earth’s Future, which publishes interdisciplinary research on the past, present and future of the planet and its inhabitants.

The trend held up even when wealth was taken out of the picture. When residents had a similar income, non-white neighborhoods still faced significantly higher temperatures than white ones in 71% of the counties.

“Urban climate is different from temperatures outside the city,” explained the study’s co-author Susanne Benz, an environmental scientist who conducted this research at the University of California, San Diego and is now at Dalhousie University. “Inside the city, temperatures are affected by the buildings surrounding you and by the surface of the streets.” Dark pavement absorbs sunlight and releases the heat at night, while trees and other vegetation cool an area through transpiration, when they release water vapor through pores in the leaves.

High Temperatures Can Be Deadly

Heatwaves cause over 700 deaths a year in the United States. When heat and humidity are so high that a body can no longer cool itself through perspiration, heat stroke can set in, rapidly causing brain and organ damage. People who are older, have certain chronic health conditions or are physically exerting themselves are most at risk. A few degrees difference can mean life or death.

Using data from NASA and the Census Bureau, Benz and co-author Jennifer Burney, an Earth scientist at the University of California, San Diego, found that in 76% of counties with more than 10 census tracts, poorer neighborhoods were notably hotter than wealthier ones, primarily due to physical differences—more pavement and people and fewer trees. Areas with a larger percentage of people of color or where people had less education also experienced higher temperatures.

Benz and Burney saw the same patterns playing out in less developed areas as in urban ones. “It turns out that even your tiny towns have the same disparities,” Benz said, “and this was something that really shocked me.”

“The findings are really quite staggering,” said Jeremy Hoffman, a climate scientist and chief scientist at the Science Museum of Virginia, who was not involved in the research. “These disparities exist across virtually every built environment in the country. Money doesn’t grow on trees, but it is certainly concentrated underneath them across the U.S.”

To compare your neighborhood to others, visit https://sabenz.users.earthengine.app/view/urbanheatusa.

How To Beat Urban Heat

There are solutions. Hoffman suggests planting trees at parks, bus stops and along pedestrian thoroughfares and providing incentives for green or white reflective roofs to cool buildings. These initiatives could dovetail with urban agriculture programs, solar panel installation, workforce development and other programs to more holistically address racial inequality.

The new analysis provides information for policymakers and establishes a way to evaluate the success of policies designed to address urban heat. Now that officials can recognize and measure urban heat disparities, they can try to fix them.

Learn More

For further facts and to see the entire report, go to news.agu.org.

“Non-white neighborhoods are hotter than white neighborhoods even when wealth is not part of the picture. When residents had a similar income, non-white neighborhoods still faced significantly higher temperatures than white ones in 71% of the counties in thttps://bit.ly/3kDVs39“